Diversity In The Stem Workforce Varies Widely Across Jobs

Content

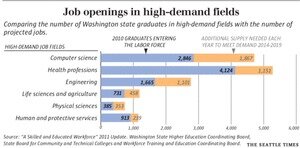

The demand and supply of STEM workers vary by market and location in much the same way that the demand and supply of taxicabs and passengers do. Just as there are separate lines for taxicabs that accept credit cards versus ones that do not, there are distinct lines for each type of STEM occupation. A queue of waiting taxis may be a common sight at an airport, but outside a hotel it may be more common to see a queue of waiting passengers. Analogously, the demand for petroleum engineers in Texas is different from the demand for petroleum engineers in Massachusetts. The upshot is that there may not be a STEM “crisis” in all job categories, but instead just in select ones at certain degree levels and in certain locations. But, 38% of women and 53% of men with a college major in computers or computer science are employed in a computer occupation.

Are STEM majors actually harder?

STEM majors, on average, spend 16.5 hours preparing for class (doing homework, lab work or reading) compared to humanities, who spend just 14 hours per week. That means STEM majors work more than 17 percent harder on homework than humanities.

The suggestion by the president’s Jobs and Competitiveness Council that the nation’s economy is hampered by a shortage of engineering graduates also earns doubt. To evaluate this claim, it is only necessary to turn to another of the president’s councils, the Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. According to its analysis of the engineering workforce, the nation is currently graduating about 25,000 more engineers every year than find work in that field. Moreover, it seems that some companies suffer from a surfeit of technology workers.

Panel Warns Us Faces Stem Workforce Supply Challenges

Foreign-born scientists and engineers currently comprise a considerable fraction of the U.S. Committee Chair Eddie Bernice Johnson (D-TX) opened the hearing by citing various benchmarks of U.S. competitiveness in science and technology. She lamented the stagnant performance of U.S. students in math and science assessments as well as the persistent underrepresentation of women and minorities in STEM fields, saying it could lead to “dire workforce shortfalls” if not addressed soon. She also noted the U.S. is behind several other countries in terms of the share of GDP spent on R&D and said China “likely” surpassed the U.S. in total R&D spending last year.

- In the IT industry, a common view among managers and workers is that the occupation was great for their generation but the ride is now over, and they would not recommend an IT or engineering career to their sons and daughters.

- Our interviews with engineers, technology managers, and others in STEM fields find a broad and deep consensus that these fields are not highly attractive as careers financially or for employment stability.

- The threat of offshoring and an influx of guest workers are paramount in their assessment of the prospects in these fields.

- My colleague Leonard Lynn and I have additional evidence from interviews and some quantitative evidence about the purported advantages of STEM training and jobs.

And among students who graduate within six years of enrollment, the number who start with a non-STEM major but graduate with a STEM degree is greater than the number who start in a STEM major and graduate with a non-STEM degree . Even in the demanding field of engineering at a top school such as Stanford University, one of every nine graduates did not start as an engineering major but transferred into the program after the first year. So, yes, some students enter college thinking they want to be a scientist or engineer and then move to another major for one reason or another, but it seems that a greater number of other students find at some point in their studies that a STEM degree is more attractive. McNutt referencedrecent datafrom the National Science Foundation indicating that international enrollment in U.S. science and engineering degree programs dropped 6 percent between 2016 and 2017.

In 5 Americans Say Stem Worker Shortage Is At Crisis Levels

And women with a college degree in engineering are less likely than men who majored in these fields to be working in an engineering job (24% vs. 30%). These differences in retention within a field of study for women in computer and engineering occupations are in keeping with other studies showing a “leaky pipeline” for women in STEM. Women’s representation among the college-educated STEM workforce depends, in part, on women completing college training in STEM fields. Among college-educated workers, the share of women earning a STEM degree varies widely and generally corresponds with the share of women in these occupational clusters. Among all college-educated workers who majored in a health professions field, 81% are female. One might argue that offshoring provides some benefit to the U.S. economy , but it does not expand or strengthen the domestic STEM workforce. The only clear impact of the large IT guest worker inflows over this decade can be seen in salary levels, which have remained at their late-1990s level and which dampen incentives for domestic students to pursue STEM careers .

In September 2012, Hewlett Packard announced that it planned to lay off 15,000 workers by the year’s end, reaching a total of 120,000 layoffs over the past decade. Or consider General Electric’s recent relocation of its 115-year-old Xx-ray headquarters from Wisconsin to Beijing, after earlier expansion of its corporate R&D labs in India and China. These companies represent the general trend, in industry after industry, of locating STEM-intensive activities offshore while shrinking their U.S. workforces. IBM, for example has reduced its U.S. workforce by 30% and now has four times more offshore than domestic employees. It is thus a rather curious proposition that companies are seeking more STEM employees at the same time that they are laying off huge numbers of STEM workers and increasing the employment of offshore STEM workers who earn a fraction of U.S. salaries. It is not clear what producing another 10,000 engineers would do, especially as fewer engineering graduates find engineering jobs and salaries are flattening for all but a few fields. If there were a talent shortage, where are the market indicators that signal students there is an opportunity to pursue a career in this industry that is better than their alternatives?

Who is better in math male or female?

A recent meta-analysis of research on the performance of students from elementary age through adulthood found boys tend to outperform girls in more complex areas of math such as those involving more advanced problem-solving.

The differential retention rates of women in computer and engineering occupations is in keeping with other studies showing a “leaky pipeline” for women in STEM. Including healthcare practitioners and technicians as STEM occupations has broad ramifications for the key findings. Healthcare practitioners and technicians are largely women, thus their inclusion boosts the overall representation of women in the STEM workforce. These health-related occupations also have somewhat larger shares of black workers and smaller shares of Asian workers compared with other STEM occupations, which affects the racial and ethnic composition of the overall STEM workforce. Among college-educated workers who majored in a STEM field during their undergraduate education, those who majored in health professions are significantly more likely to work in a STEM occupation, so their inclusion increases figures on the retention of STEM-trained workers. Even so, among college-educated workers, women who majored in computer science or related computer fields are less likely than men trained in those fields to be working in computer jobs. Similarly, women who majored in engineering are less likely than men to be working in engineering jobs.

My colleague Leonard Lynn and I have additional evidence from interviews and some quantitative evidence about the purported advantages of STEM training and jobs. Our interviews with engineers, technology managers, and others in STEM fields find a broad and deep consensus that these fields are not highly attractive as careers financially or for employment stability.

Although fields such as computer programming and mechanical engineering are generally considered STEM fields, there is less consensus on areas such as medicine, architecture, science education, social sciences, and blue-collar manufacturing work. In this article, “STEM” refers to the science, engineering, mathematics, and information technology domain detailed by the Standard Occupation Classification Policy Committee, but excluding managerial and sales occupations. Under this definition, postsecondary teachers in STEM fields and lab technicians are considered STEM workers, but workers in skilled trades, such as machinists, are not. Our analysis focuses on graduates with postsecondary education within this STEM domain. The first area to consider is the broad notion of a supply crisis in which the United States does not produce enough STEM graduates to meet industry demand. In fact, the nation graduates more than two times as many STEM students each year as find jobs in STEM fields.

Guest workers provide benefits to the companies that hire them in the form of lower wages, but there is little evidence to suggest that they strengthen the nation’s science, engineering, or technology workforces. Moreover, it is underrepresented minorities and recent permanent immigrants who are most likely to be disadvantaged through lower-paying jobs and job loss due to newly arriving guest workers. Remarkably, the number of STEM majors, from first year through graduation, expands rather than shrinks.

Students Dont See The Value Of Stem Careers

The authors suggest that, though increasing U.S.-born STEM workers is essential, foreign-born STEM workers, who tend to be slightly younger than the overall STEM workforce, may still be required in the U.S. to meet future labor needs. Among college-educated workers with training in other STEM fields, however, men are often more likely than women to be working in jobs directly related to their major field of study. For example, 38% of women and 53% of men who majored in computers or computer science are employed in a computer occupation. Women with a college degree in engineering are less likely than men who majored in these fields to be working in an engineering job (24% vs. 30%).

This fact sheet from the American Immigration Council analyzes data from the American Community Survey to give an overview of the occupational, gender, educational and geographic distribution of foreign-born STEM workers in the United States. It offers a side-by-side comparison of two sets of STEM occupations based on two different STEM definitions. The total number of STEM workers in the U.S. has nearly doubled since 1990, with one-fifth to one-quarter of the STEM workforce being foreign-born in 2015. Foreign-born STEM workers have made significant contributions to innovation and productivity, e.g. 25 percent of high-tech companies founded between 1995 and 2005 had at least one immigrant founder. The foreign-born also dominate among those with advanced degrees — immigrants make up the majority of STEM workers with doctoral degrees. With STEM occupations projected to grow 13 percent to more than nine million between 2012 and 2022, the U.S. will need about one million more STEM professionals than it will produce over the next decade.

The pattern is similar for blacks and Hispanics, who also tend to be concentrated in less lucrative STEM jobs, widening the measured earnings disparity. In 2015, there were around 9.0 million STEM jobs in the United States, representing 6.1% of American employment.

Legislation To Spur The Growth Of Stem Workers

Or has government policy restructured this labor market to supply seemingly endless numbers of guest workers who, coming from low-wage countries and constrained in their employment options, will understandably flock to these jobs even if wages are stagnant? With current policies that provide guest workers in numbers equal to as much two-thirds of new jobs in IT, it becomes less important for the IT industry to use the domestic market to supply its workforce. The petroleum industry also claims to be experiencing a sharp rise in its demand for petroleum engineers as new exploration increases and its current workforce starts to retire. But unlike the IT industry, petroleum companies stepped up the wages offered to new graduates by 40% over five years. These natural experiments provide strong evidence that STEM labor markets are responsive to market signals. Foreign-born workers in the United States represent a growing share of the science, technology, engineering and math workforce in all occupational categories.

Brookings Institution found that the demand for competent technology graduates will surpass the number of capable applicants by at least one million individuals. The BLS noted that almost 100 percent of STEM jobs require postsecondary education, while only 36 percent of other jobs call for that same degree. Many organizations in the United States follow the guidelines of the National Science Foundation on what constitutes a STEM field. Eligibility for scholarship programs such as the CSM STEM Scholars Program use the NSF definition. In the Philippines, STEM is a two-year program and strand that is used for Senior High School , as signed by the Department of Education or DepEd.

In the IT industry, a common view among managers and workers is that the occupation was great for their generation but the ride is now over, and they would not recommend an IT or engineering career to their sons and daughters. The threat of offshoring and an influx of guest workers are paramount in their assessment of the prospects in these fields. In life sciences, the perception is much the same, as most Ph.D. graduates will be likely to hold one or two postdoctoral positions, earning $50,000 a year for half a decade or more, and then be thrown into a poor job market in their mid-30s. These might be careers worth pursuing if one loves the work and is willing to play the job lottery, but they are not occupations attractive to those for whom the pay and conditions weigh strongly in the decision. Depending on the definition, the size of the STEM workforce can range from 5 percent to 20 percent of all U.S. workers.

The STEM strand is under the Academic Track, which also include other strands like ABM, HUMSS, and GAS. The purpose of STEM strand is to educate students in the field of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, in an interdisciplinary and applied approach, and to give students advance knowledge and application in the field. After completing the program, the students will earn a Diploma in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. In some colleges and universities, they require students applying for STEM degrees (like medicine, engineering, computer studies, etc.) to be a graduate of STEM, if not, they will need to enter a bridging program. This queuing theory framework provides a novel approach to looking at the STEM labor market and the STEM crisis-versus-surplus conundrum.

Thus, in two occupational clusters with particularly low shares of women, retention of those who appear to meet a key requirement for job entry appears to be lower for women than for men. In spite of the earnings advantage that STEM workers have over non-STEM workers, the gender wage gap is wider in STEM occupations than in non-STEM jobs. This is partially because women are clustered in lower-paying STEM jobs in the health care industry and underrepresented in the more lucrative fields of engineering and computer science.

For the 180,000 or so openings annually, U.S. colleges and universities supply 500,000 graduates. Accepting that STEM field definitions are overly restrictive and that in even marginally related occupations there could be a productive use of workers with STEM degrees, these numbers still represent a 50 to 70% greater supply than demand. Engineering has the highest rate at which graduates move into STEM occupations, but even here the supply is over 50% higher than the demand. IT, the industry most vocal about its inability to find enough workers, hires only two-thirds of each year’s graduating class of bachelor’s degree computer scientists. By comparison, three-quarters or more of graduates in health fields are hired into related occupations .